THING 010 : ARKHE

LAUREN BURROW

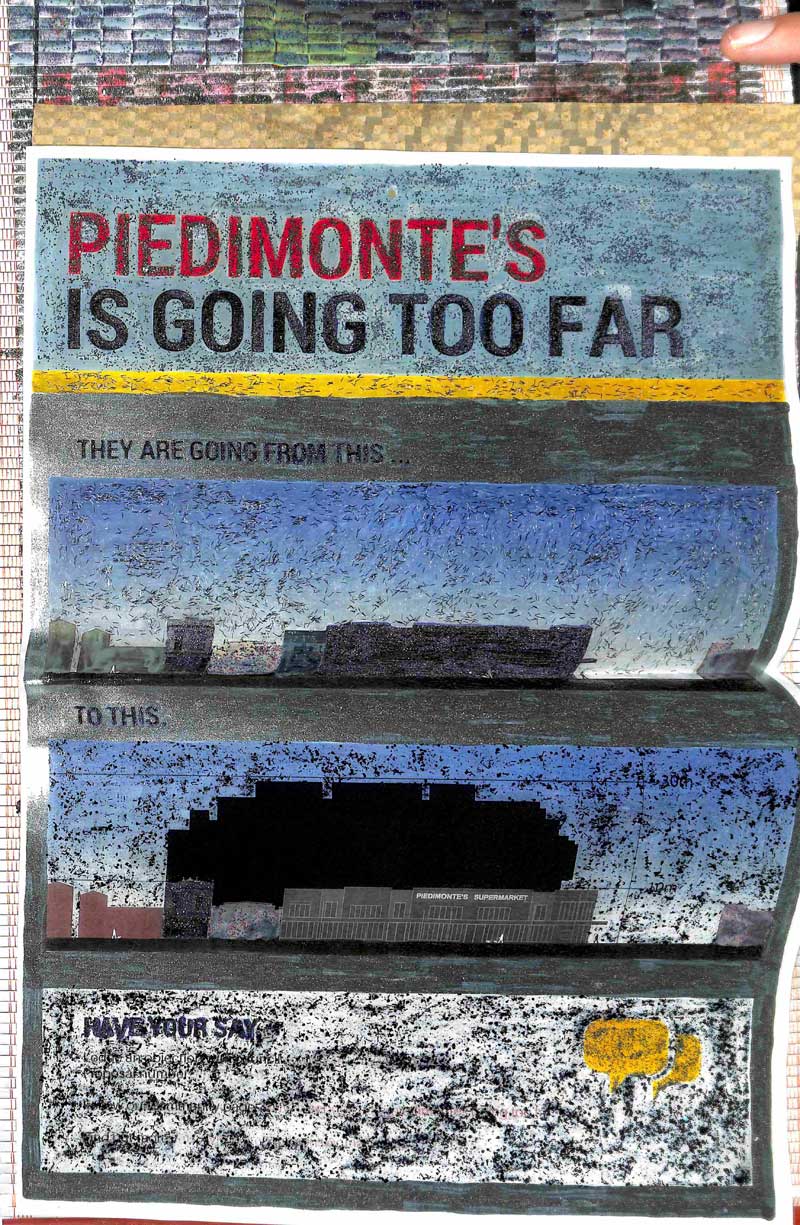

FUGITIVE CALENDAR

RICHARD KENNEDY

UNDER THE INFLUENCER

Dear World:

I can’t make it

I have been invited for “Wine & Spirits”

… An evening with a medium

Under the influence of Miss Cleo and Sutter Home

Little Sylvia Pabst

I see expansion. Burned image with collagen

Verified by application

Face Painters

A-(I)t girls

Attractivists

And the occasional Simone Biles

American as three buck chuck and corndogs

With packaging of fine wine

Blocked Light

Tumblr Umbrella

Marginal maneuvers

The view outside

I was drunk in love

But now I’m just wasted

I thought I was love sick

But now I’m just fading

Nothing has changed, it’s only the internet

Something refrains, humans are limited

Nothing is true, until truth is set free

Civilization jungle

Alien technology reveals

Homosexualiens

Swirling Storms on Jupiter poles

Mayans ruining colonized lies, ancient city

“Grossly Underestimated”

If it’s the end, is it disaster?

If it’s the end light will come after.

I was drunk in love

But now I’ve misplaced it

I thought I was love sick

But now I’m just shameless

Image captured by Whitney Vangrin

DAN HOUGLAND

SARAH CAMERON

UNTITLED

DIANE NGUYEN

FLESH BEFORE BODY

SC

UNTITLED

the sisters lay side by side in the crumpled and bloody sheets, crucified on a pair of scissors that slit through them like a double-edged paper cut. the heat between them was as palpable as the cold marble cathedral interior of their love, as it is with sisters, who are double.

scar lay back and stretched out on the icy flags, staring up at the blank altar beneath the body of christ, whose arms, held up by the rigid cloaked god, seemed to steel themselves to hold the weight of the mortal body against the structure they leant on. she’d just come. baby knew just how to stroke her scar so that it hurt a little but just enough to excite her. she was wet like a pebble.

baby, who in her mind was elsewhere, cracked the glass she’d been drinking from and slid it down her inner thigh, playing, and tempting herself with the cool sharp shard that threatened to unfeelingly slice her open. her clit was pulsating and she felt that if she just moved the shard a tiny bit closer to her wet cunt she’d come again and again.

“the crack in the floor lies between the two black surfaces”, baby thought, looking around the church interior “and those surfaces reflect the face of the shattered mother” : in one version of the story the mother’s complexion is not porcelain, but black glass.

scar was given her scar when she became a man in another life and worked the high seas on the pretext of selling bootleg liquor and porn to sailors from a small inflatable craft. when she got inside the ship she ran a real stall inserting ball-bearings into sailor’s cocks for a high price. there was a lucrative trade in ball bearings as the insertions made the girth of the penis rippled, wider and more able to pleasure hookers, like baby and scar, who scaled the sheer steel hulls to come on board in the southern seas. it was a special trait of motormen to attach great importance to pleasuring the prostitute, perhaps because of their particular relationship with the smooth workings of the machine. the taking of the prostitute’s body required in return a performance of wild shuddering orgasmic pleasure and noises that might be drowned out by the drone of the engine, the lack of which was a terrible blow to the men’s egos. the more he paid, the more pleasure he had to give and she took the money to enjoy the exquisite tingling sensation of using and being used.

they tied her to the bed on the ship and cut out the child while she kicked and screamed and drowned in her own blood and shit. no one had told her about the involuntary crescendo of faeces that would jet forth as she was opened, that would spray up vertically, so far it would reach the mast head. it was then that she remembered the time she had shit in her pants as a kid and that it came with utter silent mortification, played out in front of the audience: the family. a part of her died that day at the mast and was reborn in flight. from that day on she had a beautiful hole that the screaming sea flowed out of.

NEVINE MAHMOUD

TOY FLOAT ANATOMY (PAGES 1-4) 2017

NATHANIEL DWIGHT

JENNIFER MARTIN

Slippery Photographs, Slippery Histories

This essay was originally presented during the symposium Memory and the Future convened by Jonathan Miles at the Royal College of Art (London, UK) in February 2018.

/1/ The Colour Line, Futures, and Rewritten Histories

Historically inflicted trauma becomes dystopian when crossing the colour line. In 2014 Save The Children UK released a sensationalist advertisement created by Don’t Panic, titled ‘If London Were Syria’, also known as ‘Most Shocking Second a Day Video’1. The commercial imagines the Syrian Civil War taking place on the streets of London through the vantage of a young white British girl, Lily.

Save The Children UK, Most Shocking Second A Day Video, published on 5 March 2014

Save The Children UK, Most Shocking Second A Day Video, published on 5 March 2014

In 2016 Save The Children released a sequel commercial, ‘Still The Most Shocking Second A Day’2, which follows Lily from the point we left her two years prior: still in crisis, attempting escape by boat, and taking responsibility for a young boy whose parents drowned while attempting to flee. The original commercial attracted 23 million views on YouTube in less than a week of its release; today it has over 58 million views. The ‘dystopia’, which is sometimes, as with Save The Children’s commercials, purposefully scripted to humanise historically occurring violence and traumas, set up an equation in which said violence and trauma are only rendered human and memorable in association to white subjectivity.

Save The Children UK, Still Most Shocking Second A Day, published on 9 May 2016

Save The Children UK, Still Most Shocking Second A Day, published on 9 May 2016

Similarly, The Handmaid’s Tale imagines a ‘dystopian’ near future in which gendered violence including rape, enslavement, and forced breeding is inflicted upon primarily white women within their primarily white society. This proposed dystopia, the what if propelled from a narrative that equally purports a situational difference and distance from our lives, is reliant on its application to whites and the orchestration of violence by whites. ‘To’ and ‘by’ are integral to these historically misremembered fictitiously future narratives as it is presupposed within our 21st-century society that whites cannot/do not inflict pain within their own communities, forming the fictive basis for the storyline.

The Handmaid’s Tale, Television Series, 2017

The Handmaid’s Tale, Television Series, 2017

Margaret Atwood, the writer of the original book published in 1985 and supervising producer of the current television series, wrote with the intention to link the narrative to historical antecedents. In an interview, she notes clippings saved from ‘stories of abortion and contraception being outlawed in Romania…Canada lamenting its falling birth rate, and…[U.S.] Republican attempt to withhold federal funding from clinics that provided abortion services’3 At the time of writing the novel, Atwood lived in West Berlin. In addition to being influenced by state surveillance in East Germany, she notably identifies as key source material 17th-century Puritanism in America and ‘the Nazi party’s Lebensborn program, designed to encourage a high birth rate among Aryan women’4. However, The Handmaid’s Tale bears a strong connection to another history of America, that being chattel slavery.

Numerous commentators have highlighted a passage in the original novel, which remarks in passing on the ‘resettlement of the Children of Ham’5, as the removal of blacks from the all-white storyline. Bruce Miller, creator of the contemporary television series had no intention of fully eliminating people of colour from the visual landscape of his show, reflecting instead, ‘It’s easy to say “they sent off all the people of colour,” but seeing it all the time on a TV show is harder.’6 In lieu of this original resettlement of raced characters, Miller crafted a post-racial landscape interposed sparsely with black, brown, East Asian, and South Asian bodies.

The most intimate relationships for the protagonist June are with black identifying individuals: her husband is played by a black bi-racial actor, their child a young black mixed-race girl, and her best friend is a black woman. Miller attributes the ‘diversity’ of these roles as colour-blind casting rather than intentional to the narrative. Resultantly, viewers are left with a television show that never acknowledges race, racism, or correlation to histories of racist subjugation. No character on the show mentions American chattel slavery or any other history of black oppression as a way of comprehending the realities of the Gilead regime they inhabit.

The Handmaid’s Tale, Television Series, 2017

The Handmaid’s Tale, Television Series, 2017

Black, brown, and indigenous bodies have always been used to cement power for white societies, generating wealth that has allowed their sustenance to date. Rape, extraction of natural resources—including adults and children—, pillaging, removal and resettlement, enslavement, torture, and conversion—all present within the Gilead society of The Handmaid’s Tale are processes of colonialism. Miller notably stated that race would not intersect this dystopia, reasoning, ‘When you think about a world where the fertility rate has fallen precipitously [as it has in Gilead], fertility would trump everything. And we’ve seen that: When fertility becomes an issue, racism starts to fall because people adopt kids from Ethiopia and Asian countries and from everywhere.’7

Perhaps had Miller employed any female identifying writers of colour on the staff for the programme, they may have been able to underscore the implausibility of Miller’s Gilead: in the series Gilead is a totalitarian right-wing Christian fundamentalist terrorist sect, administered overwhelmingly by white men, who overthrow the US government with the intention of eradicating human rights, and especially women’s rights for the purpose of enslaving women to rape and impregnate. They do so while also hunting and murdering individuals for their homosexuality, and intellectualism. And yet in spite of all of their principles and objectives, this theocratic regime is not racist, they in fact, do not acknowledge race at all.

The Handmaid’s Tale, The Emmys, 2017

The Handmaid’s Tale, The Emmys, 2017

Writer Angelica Jade Bastién critiques the series, citing race as its greatest failing and tying this faux-dystopian storyline to the following specific historical precedents in the US alone: the sterilization of Mexican and Mexican-American women in the 1960s and 1970s in L.A. against their will, which birthed the Chicano and feminist movements of that time, and the forced and coerced sterilization of predominantly black poor women by North Carolina’s Eugenics Board from 1929 to 19748.

More Broadly, Bastién, foregrounds links to the practices of chattel slavery including the brutalization and rape of many black women, the act of separating blacks from their children and other family, forced servitude, the renaming of enslaved peoples after the men who enslaved them, religious conversion, the banning of reading, writing, or congregating, and the use of public lynchings as enforcement of fear9. Cultural theorist Greg Tate refers directly to the black American experience as a ‘science-fiction experience’10. The relevance, the proverbial draw that drops, is one dismayed to see such horrors enacted against the principally white characters dressed in the red robe and white bonnet of Atwood’s story.

The white body as sufferer renders said suffering audible. The white body of a ‘dystopian’ narrative renders the imaginary nature of said ‘dystopia’ fathomable. The white body is locus, its subjectivity necessary for envisioning that, which normally remains beyond ‘the Veil’ as theorised by W.E.B. Du Bois or conscious concern. However, in only recognising violence inflicted onto white bodies, in taking the histories and present impositions of predominately black and brown peoples and recasting this as a whitewashed future that we as a society must avoid by any means necessary, the fissure swells. The viewer whom these narratives inherently reject and refuse as their audience is left with a transmutation of their histories and lived impositions; we are hollowed out and misremembered. The consumer of these narratives remains behind ‘the Veil’, impermeable and unmoved in the present, cautiously envisioning a future that might touch them.

1. Wikipedia, If London Were Syria (2017) <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/If_London_Were_Syria> [accessed 22 January 2018].↩

2. SaveTheChildren, Still the Most Shocking Second (2016) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nKDgFCojiT8> [accessed 22 January 2018].↩

3. Rebecca Mead, ‘Margaret Atwood, The Prophet of Dystopia’, The New Yorker, 17 April 2017, <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/04/17/margaret-atwood-the-prophet-of-dystopia> [accessed 20 January 2017]. ↩

4. Sain Cain, ‘The Handmaid’s Tale on TV: too disturbing even for Margaret Atwood’, The Guardian, 25 May 2017, < https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2017/may/25/the-handmaids-tale-on-tv-too-disturbing-even-for-margaret-atwood> [accessed 20 January 2017]↩

5. Ana Cottle, ‘”The Handmaid’s Tale”: A White Feminist’s Dystopia’, The Establishment, 17 May 2017, < https://theestablishment.co/the-handmaids-tale-a-white-feminist-s-dystopia-80da75a40dc5> [accessed 20 January 2017].↩

6. Shannon Gibney, ‘Race, Intersectionality, and the End of the World: The Problem with The Handmaid’s Tale’, The Nerds of Color, 10 May 2017, <https://thenerdsofcolor.org/2017/05/10/race-intersectionality-and-the-end-of-the-world-the-problem-with-the-handmaids-tale/> [accessed 20 January 2017].↩

7. ibid.↩

8. Angelica Jade Bastién, ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’s Greatest Failing Is How It Handles Race,’ Vulture 14 June 2017, < http://www.vulture.com/2017/06/the-handmaids-tale-greatest-failing-is-how-it-handles-race.html> [accessed 20 January 2017].↩

9. ibid.↩

10. J. Hoberman, ‘”Space is the Place” Offers Otherworldly Takes on Identity’, NY Times, 2 April 2015, < https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/05/movies/space-is-the-place-offers-otherworldly-takes-on-identity.html> [accessed 20 January 2017].↩

/2/ The Metamorphosis of the Slippery Poor Image

PART I

A photograph situated within a personal archive seems familiar in the sense that we usually have engaged with or are aware of the context under which the photograph came into being. Author Shawn Michelle Smith asserts in no uncertain terms, ‘Although the photograph may not be able to tell us much more about the subject that it makes visible without textual interpretation, it undeniably testifies[,] “that has been”’11. However, if a photograph exists in divergent temporalities presenting the past to the future, the likelihood of the undeniable and obtaining total knowability of the image is slim. Anthropologist Elizabeth Edwards notes that ‘Perhaps it is an ultimate unknowability that is at the centre of the photograph’s historical challenge, for we are faced with the limits of our own understanding in the face of the “endlessness” to which photographs refer.’12

Photography projects the appearance of knowability through its presumed relationship to referent as transfigured through light, paper, and chemical (also through light, sensor and data). Crucially, Elizabeth Edwards questions this knowability instead defining photography, like history as ‘concerned with the partial nature of historical inscription and understanding, the ultimate unknowability in holistic terms.’13 Photographs do not present fixed states they are altogether something much more slippery. And it’s within that greasy, oiled, and evasive crevice that we encounter memory or the act of remembering and misremembering.

PART II

I presented a photograph recently to a seminar group run by artist Andy Holden, which was part of an exercise called Tumblr Club. This image needed to be what Andy described as an ‘artefact of exceptional resonance that exists online’14 for the purpose of considering ‘the act of judgment in relation to the current proliferation and dissemination of images’15.

The image I submitted was one of four that I saved from this year’s Women’s March. Of the four photographs I saved from the onslaught of images being circulated and re-circulated through social media, this photograph was the most self-evident to me. It encapsulated the deafness and politics of narcissistic participation that for me coloured this event and that of the previous year. Yet even though I selected this image for its bluntness, this idea of an obvious document, the photograph shifted through my viewership.

My feelings about the image itself did not fluctuate, but rather my comprehension of what exactly was pictured did. As a poor image, and as part of collective socialised archiving, it lent itself to this emotional activated metamorphosis. The protester became a protester possibly wearing an outfit mimicking the costumes of The Handmaid’s Tale. The possibility for this morphing was left open by the limited view of the protester’s body and my memory of other protesters’ attire. This was reinforced by my judgment of that particularised intention of costumery, and the authored statement. Of course, such a woman would dress as a ‘handmaid’.

When putting forth this image to the group the unexpected happened in the search for understanding the resonance of the image. The protester that became the possible costume wearer again transformed into the author of The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood. Could that be Margaret Atwood, knowingly pairing down the aesthetic that characterises her work? Just as quickly as the idea was thrown out, the Google search of Atwood rejected this possibility as a too thrilling coincidence. The image was partially restored to its initial reading,

but the remembering and misremembering that metamorphosed the image has continued to captivate me.

This image that is torn from its original source, framed solely within a context of modern politics and visual language, slipped and slid through an affirmation of a “that has been”. The image lent itself to a process of the endless possibility of contextualization: the author’s words were re-contextualized by its reader, the act of protesting re-contextualized by the placard, the protester’s outfit re-contextualized by the event, and the photograph’s subject itself re-contextualized by the sum of its aesthetics. It is an image that while without a geographic tag or timestamp affirms itself to be of the now, of the United States or at least citing the U.S., and specific enough to be tied to this particular event, the Women’s March. Yet, other attempts to stabilise or confirm this photograph lead to a collapse of knowability. Indeed the image alternatively presents the oily facade by which a photograph can slip from our grasp into an uncertain state, into ‘ultimate unknowability’.

11. Shawn Michelle Smith, Photography on the Color Line: W.E.B. Du Bois, Race, and Visual Culture (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2004), p. 248. ↩

12. Elizabeth Edwards, Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums (Oxford and New York: Berg, 2001), p. 10. ↩

13. ibid., p. 19. ↩

14. Andy Holden, ‘Cross School Group starting next week’, 2018.↩

15. ibid.↩

Bibliography

- Bastién, Angelica Jade, ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’s Greatest Failing Is How It Handles Race,’ Vulture, (June 2017), < http://www.vulture.com/2017/06/the-handmaids-tale-greatest-failing-is-how-it-handles-race.html> [accessed 20 January 2017].

- Cain, Sain, ‘The Handmaid’s Tale on TV: too disturbing even for Margaret Atwood’, The Guardian, (May 2017), < https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2017/may/25/the-handmaids-tale-on-tv-too-disturbing-even-for-margaret-atwood> [accessed 20 January 2017].

- Cottle, Ana, ‘”The Handmaid’s Tale”: A White Feminist’s Dystopia’, The Establishment, (May 2017), < https://theestablishment.co/the-handmaids-tale-a-white-feminist-s-dystopia-80da75a40dc5> [accessed 20 January 2017].

- Edwards, Elizabeth, Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums (Oxford: Berg, 2001).

- Hoberman, J., ‘”Space is the Place” Offers Otherworldly Takes on Identity’, NY Times, (April 2015), < https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/05/movies/space-is-the-place-offers-otherworldly-takes-on-identity.html> [accessed 20 January 2017].

- Holden, Andy, ‘Cross School Group starting next week’, 2018.

- Gibney, Shannon, ‘Race, Intersectionality, and the End of the World: The Problem with The Handmaid’s Tale’, The Nerds of Color, (May 2017), <https://thenerdsofcolor.org/2017/05/10/race-intersectionality-and-the-end-of-the-world-the-problem-with-the-handmaids-tale/> [accessed 20 January 2017].

- Mead, Rebecca, ‘Margaret Atwood, The Prophet of Dystopia’, The New Yorker, (April 2017), <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/04/17/margaret-atwood-the-prophet-of-dystopia> [accessed 20 January 2017].

- SaveTheChildren, Still the Most Shocking Second (2016) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nKDgFCojiT8> [accessed 22 January 2018].

- Smith, Shawn Michelle, Photography on the Color Line: W.E.B. Du Bois, Race, and Visual Culture (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2004).

- Wikipedia, If London Were Syria (2017) <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/If_London_Were_Syria> [accessed 22 January 2018].